Manantial del Rey or El Chorrillo?

During the colonial period until well into the 19th century, the water supply of Panama City was a critical issue […]

During the colonial period until well into the 19th century, the water supply of Panama City was a critical issue in daily life. In the old settlement of Panama la Vieja, vestiges of cisterns built to supply water to its inhabitants remain. Today, it is possible to visit the Archaeological Site of Panama Viejo and observe the cistern of the nuns of La Concepción. In those times, water was a business of the convents.

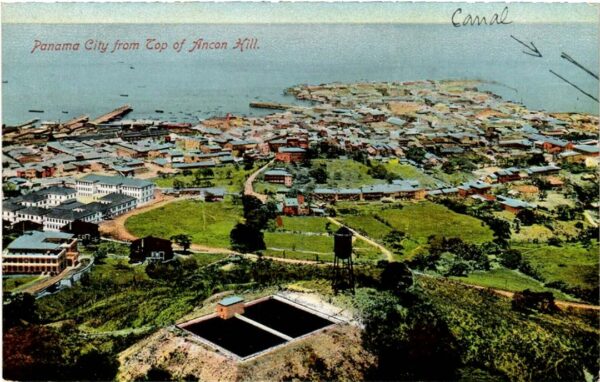

After the destruction of the first city of Panama, it was moved to Ancon, where the water problem persisted. The new water source was called Chorrillo del Ancon.

The King’s Spring

In previous issues, we documented that the city of Panama – in its new settlement of Ancon – and during the first four lustrums of the XIX century, did not present major changes after two centuries of colonial history.

The new Panama City, with its new location and new problems, such as the permanent supply of water for its inhabitants. During the first two hundred years, the city suffered many fires. There are records of three fires in the eighteenth century and seven in the nineteenth century. (Castillero, 2014).

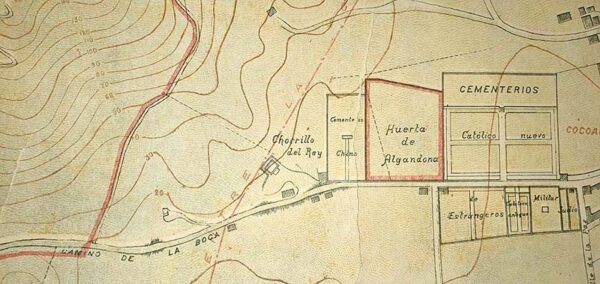

In a map that rests in the archives of the President Roberto F. Chiari Library of the Panama Canal, it is possible to identify the city’s water source called El Manantial del Rey (The King’s Spring). The trickle of fresh water that gushed from the slopes of Ancon Hill, was a spring or waterhole, and also gave its name to the iconic neighborhood of El Chorrillo.

Stories to tell

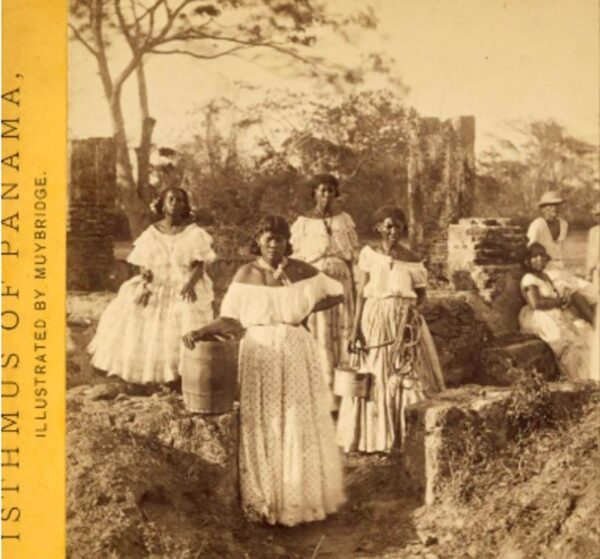

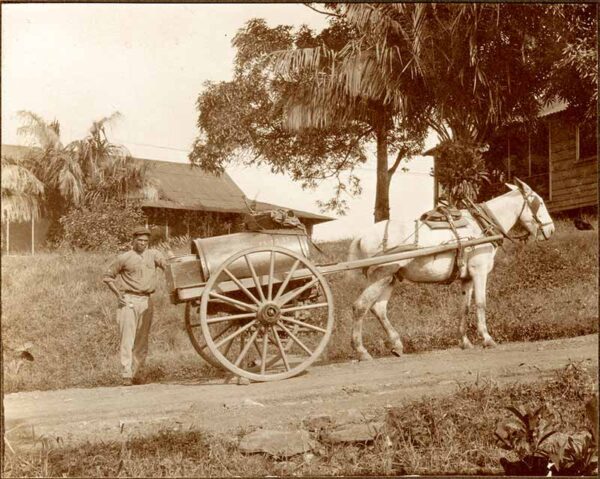

Interesting photographic documents from the late 19th century also record the watering activity carried out by women. In the untold stories of the city, a gender bias persists: it was enslaved women of African origin who were in charge of quenching the thirst of the city’s inhabitants.

The poetic song

The Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty led to the construction of the city’s aqueduct being included in the contract for the construction of the Panama Canal. This consisted of a cast iron pipe 16 inches in diameter and 16 kilometers long, which carried water from the reservoir of the Rio Grande River, near Culebra, to Panama City and surrounding communities.

This caused the Manantial del Rey or El Chorrillo to be closed. The historic spring stopped supplying the city at the beginning of the 20th century.

Amelia Denis de Icaza, in her poem Al Cerro Ancon, exclaims with nostalgia in a verse that says, “What became your Chorrillo? Your stream dried up when a stranger stepped on it, its crystalline and beneficent source sank into the abyss of non-being”. In Amelia’s verses, the construction of the aqueduct by the Americans causes El Chorrillo to disappear from memory.

In the most recent episode of the Panama Canal podcast, Así pasó, we talk with Panamanian archaeologist Carlos Fitzgerald, who unveils secrets of the ancient Manantial del Rey. The mythical Chorrillo emerges again among the voices of Panamanians, to continue weaving our lost history. We talked about its exact location and we talked about the forces that dried up its current and, possibly, to answer in which of the abysses of non-being did it sink us?