Water that comes from the wind

An invention with an Inca name and seal promises to solve the water crisis in communities without aqueducts and infrastructure. Learn the story of Max Hidalgo and how, in the 21st century, access to drinking water continues to be one of the planet’s main problems.

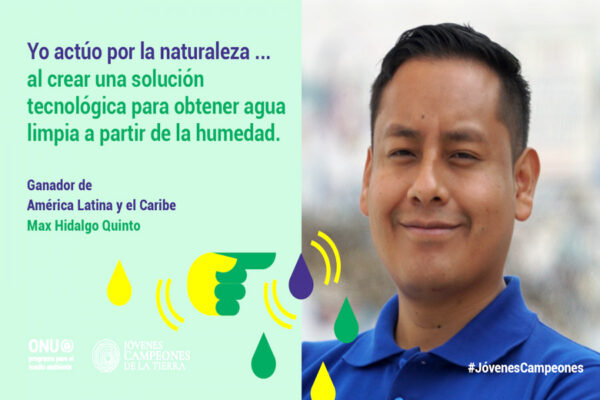

At the end of 2020, the United Nations Environment Organization (UNEP) held the Champions of the Earth contest, in which it selected seven young people from different regions of the world, who submitted their inventions to promote changes with a sustainable focus on our planet. Part of the awards consisted of providing funding from the UN to the winning projects, in addition to creating outstanding leaders in environmental management. In the selection of the Latin American and Caribbean champion, Peruvian Max Hidalgo was awarded for his invention to convert water from air.

But this is not the first time Max has unveiled his invention. In 2017, History Channel held a contest to award sustainable projects, in which more than 5,000 candidates participated. Max’s made it to the top 10 finalists, and by popular vote, he won first place.

What is this invention all about and how could it be one of the most remarkable of the decade?

El Faro spoke with Max, and here are his thoughts.

How did you become interested in designing a prototype to produce water?

I studied biological sciences. I am a biologist, microbiologist and parasitologist. I became interested in the field of inventions because I had a different perception of nature: if we want to invent new technologies, we can replicate those mechanisms of the ecosystem. That is called biomimicry; that is, imitating nature to create technologies, and that is interesting because it allows us sustainability, and that is what we should aspire to.

How does the invention work?

There are humidity levels all over the planet, even in the most arid deserts. So why not take advantage of what we have in nature to produce water? So I designed a machine to extract water from the humidity of the area, and also taking advantage of wind and solar energy. That was the basis of the invention, which can be applied in isolated communities, because conventional systems need a water source that may not even exist.

The other thing is that traditional systems need legal permits and environmental impact studies. On the other hand, such infrastructures require treatment plants, canals and pipe networks that can take years to build. There are communities that have been waiting for 30 years. So with this portable and sustainable technology, you can install it within three hours and get water.

How could you see in nature the conceptual design of an invention to produce water?

Albert Einstein said that in nature we can find the answer to all scientific and technological challenges, even those of everyday life. In the case of my invention, there are insects that capture moisture from fog and accumulate droplets on their backs by means of microfilaments. The insect then stretches one of its legs over its back and the water flows into its mouth. In the invention, centrifugal force is produced by the spinning of the blades and a condensation system collects water from the atmospheric fog.

Tell us about the background

When I was in college, in an environmental microbiology class, we analyzed the quality of water delivered by tanker trucks to different communities without drinking water. One of them was the town of Chosica (Lima). Then, we took water samples from the wells where the families stored the water from the tanker trucks, and we realized that the water was three times more contaminated than the permissible limit for human consumption. We complemented the study with bibliographic sources, and when analyzing the data, I read that every 21 seconds, a child dies in the world from drinking contaminated water. That was the first motivation to design a prototype with unconventional technology. Four years have passed since then.

Is electricity needed?

The invention uses hybrid energy: wind power supplemented by a solar energy source. In this way, we ensure that people have access to water in all circumstances. On the other hand, we have enhanced the technology and have the capacity to produce up to 350 liters of water per day. Now we are working on the production of 1,000 liters of water per day so that it can be used in family agriculture and forestry projects.

And the scope?

We have two projects aimed at two needs: Yawa Community (for human consumption), and Yawa Forest (for agriculture, irrigation and green areas projects). The one we are commercializing is Yawa Forest. To the Yawa Community we must install a sensor that determines in real time the water quality, and also, to have the certainty of the moment when the filter must be replaced. The family is expected to be able to download the application on their cell phones to track the water quality and make the replacement in a timely manner. It has not been easy, as we have gone through innovation processes. We have manufactured four different types of technology until we had a commercial one. Currently, we are manufacturing 10 more to be placed in other regions.

What does Yawa mean?

Yawa comes from the composition of two words from the language of the Incas, Quechua: yaku (water); wayra (wind). Joining the first two syllables of each word we get Yawa, that is, water of the wind.

How many people are accompanying you in this adventure?

We are eight people and we add volunteers so that we can cover other regions. Now we have a very symbolic project: we want to plant trees using Yawa technology and commemorate those who have died because of Covid-19. We are living a turning point in which we must reconcile with nature, and that is the reason for this reforestation project, which has a sustainable approach and because if we do not learn, more pandemics will come.

Tell us about the challenges.

There are several, but mainly the technology. For example, for some parts, we do not have the machinery and we have to buy some electronic components. However, we are not lagging behind. We have set up a workshop to look for ways to temporarily solve and continue looking for resources (sponsors or investors) to promote this invention on a larger scale.

The virtual interview (as it is the fashion these days) led to the Canal. Max has never been to our country and wants to know the waterway, so we extended a cordial invitation to know a work that also has a sustainable approach and culture. And that’s what it’s all about: that each person and organization, from his or her own perspective, promotes the protection of the Earth and its inhabitants. The world needs more projects like Yawa… a name that evokes our past to ensure our future.