The maps of the President Roberto F. Chiari Library

Where does the inspiration to write a work come from? For Marixa Lasso, author of “Erased“, a book about the […]

Where does the inspiration to write a work come from? For Marixa Lasso, author of “Erased“, a book about the process of depopulation suffered by the towns near the route where the Canal was built, inspiration came to her in a casual and unsuspected way. Walking through the halls of the President Roberto F. Chiari Library, she was captivated by the pastel colors of a huge 1912 map showing the municipalities that existed in the former Canal Zone. That map, the Property Map of the Canal Zone, was the trigger to ask herself: What was there before the creation of those municipalities? How were they divided back then?

That answer led him to a very striking document, the Plan général du Canal: avec indication du project. Made in 1881 and measuring 2.31 m2, this map shows in detail the original line of the interoceanic train inaugurated in 1855, and all the stations and towns through which it passed. Some of the names that appear, such as Corozal, Miraflores and Paraíso, are used today, but there are also towns that awaken nostalgia, memories and regrets. There are names such as Gorgona; the predecessor of the present town of Gorgona on the Pacific Coast, Matachín and its legend linked to collective suicides, and Emperador, from where a young Philippe Bunau-Varilla tried to manage the construction of a canal that was destined to fail. In this letter, rivers such as the Grande, the Chagres and all of its tributaries jump to the eye.

The collection

The President Roberto F. Chiari Library has 663 maps, including originals and copies. The library staff shares compendiums of copies of maps dating from the sixteenth century onwards to researchers and history buffs who visit the library.

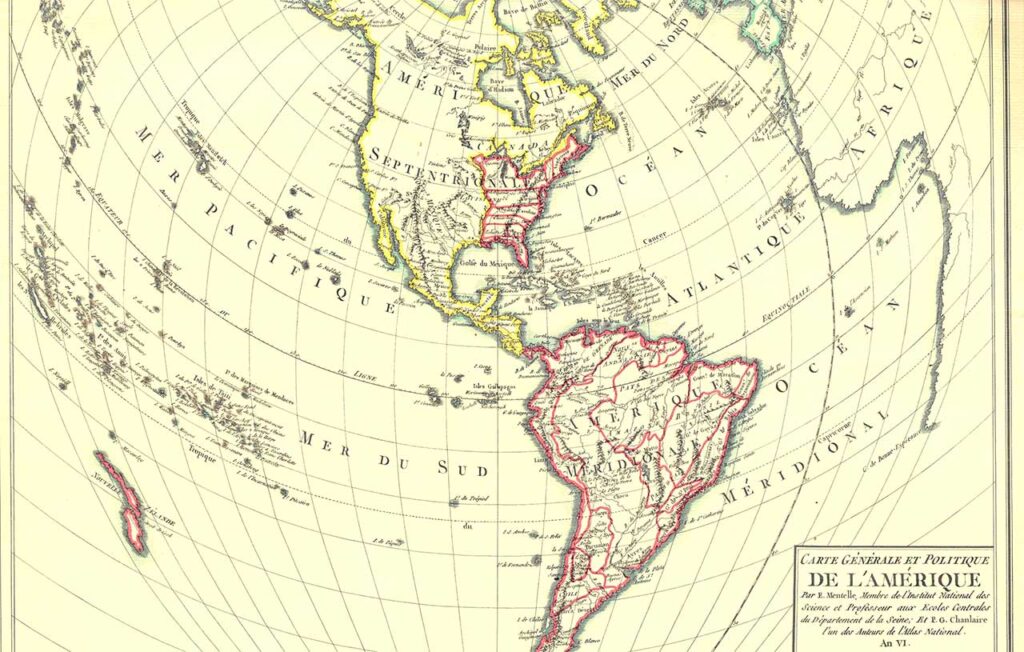

The oldest original map in the library is the Carte Générale et Politique de La Amérique, dating from 1779. The map shows in great detail the region of South America, Central America, Mexico, the eastern United States, and shows in red the political subdivisions of the time. It is interesting to note the limited knowledge of the interior of North America, and Alaska shown on the map.

Peculiarities

A striking piece on display is the famous Thomas Harrison map that delimits the lands belonging to the Panama Railroad Company and was made in 1857. To appreciate it is to enter a city that still conserved its walls and that, beyond those exclusive limits, a new city was being born, made up of enormous estates identified by the surnames of their owners. For example, part of what is now Plaza 5 de Mayo was a farm belonging to José del Carmen Rebero; and what is now the San Felipe Neri market was bought by the railroad company from a man with the surname Bermúdez. Don José Marcelino Hurtado owned a farm that encompassed all of Calidonia, and Bellavista and La Exposición were mangroves known as “El Atillo”.

The large amount of land belonging to Mr. William Nelson, who owned the entire coastline where Balboa Avenue would pass, as well as the future neighborhood of El Chorrillo and the Barraza area, is noteworthy. It can also be seen that on the slopes of Ancon Hill, there is a parcel of land owned by Ran Runnels, a former Texas Ranger who was hired by the railroad company. His services were contracted to rid the area of a band of criminals who robbed and murdered gold prospectors crossing the Isthmus on their way to and from California. Runnels was given carte blanche to solve the problem and perhaps the remedy was as bad as the disease.

In the opinion of expert researchers who have examined these maps, one of the most valuable is the 1904 map of Panama City, better known as the Bertoncini map, after its author’s surname. Hand painted, and detailing the streets and main buildings that were in what is now known as the Casco Antiguo, it also shows the buildings of the Ancon Hospital in the north, and to the west the Catholic cemetery, orchards, mangroves and details the location of the Chorrillo del Rey, a source of fresh water that came from the Ancon Hill. Scanning this map, you can see details such as the Panama Canal Company buildings painted in red, yellow and gray buildings of Panamanian residents and green everything related to parks and mangroves. All this with the Pacific Ocean as a monumental frame.

Detailing the passage of time

Maps help us understand the world we live in and give us the opportunity to learn how our environment has changed over time. That is why reviewing the maps of the canal route year by year is to discover how one of mankind’s greatest achievements took shape. The best source to verify this miracle is the Canal’s annual reports. These reports, especially those that appeared between 1907 and 1921, show maps that are authentic works of art due to their level of detail and preparation. These reports contain not only technical and economic information, but also information on the demographic situation of the population, photos of the life of the people and progress in the sectors where most of the work was being done. A great starting point for those interested is the 1909 annual report.

Maps, reports and many other historical documents can be consulted in person at the President Roberto F. Chiari Library located at the Ascanio Arosemena Training Center (Balboa) from 7:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Monday through Friday.