The dilemma of negotiations

The President of the United States, in front of a group of supporters, comes clean. He mentions the number of […]

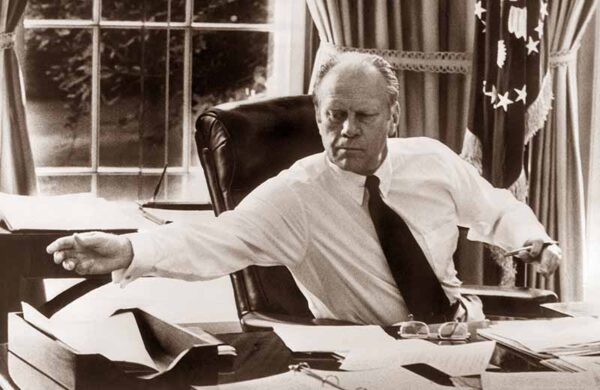

The President of the United States, in front of a group of supporters, comes clean. He mentions the number of dead as a result of the riots. He points out that his “national defense interests” in the conflict zone will not be abandoned. He stresses that this is a problem that three presidents have already been involved in and a solution is expected to be found. The president is Gerald Ford. The year is 1976 in Peoria, Illinois, and the issue at hand is the ongoing negotiations of the new treaties concerning the Panama Canal. What Ford does not know is that Panama will become one of the most important political issues of the coming year.

Panama in the 1970s

With less than 2 million people, an annual growth rate of 1.6%, an illiteracy rate of 20.7% in the cities and 33.6% in the interior, Panama finds itself in one of the most convulsive periods of its young history, in an already extremely convulsive region. The government of General Omar Torrijos Herrera is viewed with suspicion by the White House, largely due to his constant flirtations with leftist countries and movements. Torrijos’ two main goals, which frankly complement each other, are to modify the issue of Panamanian sovereignty and to improve the nation’s ideology.

Source: www.cnn.com

Perhaps the most important merit that can be attributed to Torrijos was to turn the scope of the negotiations for Panamanian sovereignty from a struggle between a power and a small Central American country to one of global scope.

For example, by meeting with Fidel Castro, Marshal Tito and Juan Domingo Perón, as well as throwing his support behind causes such as Belize’s independence, Torrijos’ image grew, and thus, the Panamanian cause on an international level. Likewise, Panama teamed up with the leaders of neighboring countries: Alfonso López Michelsen, Daniel Oduber and Carlos Andrés Pérez, presidents of Colombia, Costa Rica and Venezuela, respectively, who gave unconditional support to the Panamanian cause.

It was a foregone conclusion that talks between Panama and the United States would enter a new phase after the 1976 elections. The new U.S. president would have to engage in talks with a government that had as its helmsman someone with views, characteristics and attributes they had never had to deal with before.

The United States of America in the 1970s

In 1976, Ronald Reagan, running for president in the Republican primary, looks for ways to attack incumbent Gerald Ford politically. Reagan lacks a specific issue to serve as a counterweight with which to attack Ford, but he finds it in the discussions on Canal sovereignty. His position on Panamanian ambitions can be summed up in the phrase: “We bought it, we paid for it. We built it and we intend to keep it“. Reagan singled out Ford as weak in the face of Panama’s demands, and claimed that the Canal Zone was similar to the states of Alaska and Louisiana (territories purchased from Russia and France, respectively).

These statements, quickly denied by Ford and the State Department, would set the tone for the upcoming debates, both in the Republican primaries and in the presidential debates. The status of the Canal Zone and the future of the Canal were increasingly permeating the collective consciousness of the United States.

Everything seemed to indicate that, unless Ronald Reagan won the election, a new Panama Canal treaty would be signed soon. In the end, Gerald Ford would win the Republican nomination and Reagan’s dreams would be dashed. Panama and the United States would prepare for a new round of negotiations.

However, few expected that the future treaty would so profoundly alter the status of the Canal and its Zone.

A new president

On January 20, 1977, Democrat James (Jimmy) Carter became president with a political vision that had the defense of human rights as its guiding principle.

Carter has a new ethical vision of how to behave internationally, and wants to give an image of moral cleanliness that contrasts with the Nixon administration, which was linked to the Watergate case. The new treaty talks begin on February 13 on Contadora Island and then move to Washington D.C. on March 13. Carter knows he will have a difficult road to pass the new Treaties. In his memoirs, he mentions that “a new treaty was absolutely necessary. I was convinced that we needed to correct an injustice.”

Source: Wisconsin Public Radio

Finally, the new treaty

The signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties on September 7, 1977, is often seen as an example of effective communication, understanding and compromise, but getting to that point involved a battle that, in Torrijos’ case, was against a power he himself was not confident of defeating. For his part, Carter had to fight a battle with both Congress and the U.S. electorate, most of whom were against the treaties. This dented his credibility as president and would affect his reelection aspirations in the long run.

The U.S. Senate ratified the treaties by only one vote, 51 in favor and 49 against. In the months leading up to the treaties, the points for and against the treaties were remarkable. Carter went so far as to be clear and concise as to point out that “we do not own the Panama Canal Zone. We have never had sovereignty over it. We have only had the right to use it,” and maintained that “Theodore Roosevelt, who was President when the United States built the Canal, saw history itself as a force. He knew that change was inevitable and necessary. Change is growth. The true conservative, he once remarked, keeps his faith in the future.”

Within a year and a half, the issue of the future of the Canal and its zone had finally entered a period of calm. Negotiations were no longer a dilemma. The demands of a small but proud people had, in part, been met. How could Panama convince the most powerful country in the world to hand over such a significant asset, such an important maritime and military crossroads as the Panama Canal, to a small Central American country? Perhaps, David McCullough, author of the most consulted book on the construction of the Panama Canal, “The Path Between The Seas”, can give us the best answer, when Carter, in front of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee said: “The treaties are a synthesis of the policy expressed by four consecutive administrations, Republican and Democrat; and our presence in Panama as it is presently constituted, is an anachronism. More than this, it is asking for trouble.