The Canal, Bicentennial, and the Arts

The Isthmus of Panama, during the first half of the 19th century – and beyond – was the object of […]

The Isthmus of Panama, during the first half of the 19th century – and beyond – was the object of a series of European expeditions aimed at describing the territory, its geography, its environment and its people. The purpose of these initiatives was to concretize the idea of building an inter-oceanic communication. The immediate and previous context is that of a colonial Panama, marked by a transitional condition; an austere city, in comparison with other viceregal headquarters such as Mexico or Peru.

To understand the development and manifestations of the arts, we talked to Pedro Luis Prados, Panamanian writer, philosopher and art critic.

How would you describe the artistic manifestations at the time of Panama’s independence from Spain?

Hispano-American societies were not homogeneous and it is not possible to establish criteria to establish uniform processes. Except for the brutality in the campaigns of acculturation, expropriation and subjugation of the American peoples during the conquest and colonization. Each region acquires its own character according to its productive function. In ours, there are no mineral riches to exploit, nor a decisive agricultural production: Panama has a transitional character and this is expressed since the early years of the Sixteenth Century when Pedrarias Davila gives it a pragmatic character as a center of expeditions to the Pacific.

This, together with the Portobelo Fairs, determines the transitional function of the Isthmus and the floating nature of its population. This explains the lack of large emblematic buildings that we find in other cities typical of a population determined to settle and develop urban space, such as Lima, Quito, Bogota, among others.

The lack of large buildings explains the poor artistic richness in religious and public buildings and in housing, as shown by the studies on residence judgments carried out by Dr. Alfredo Castillero Calvo. The architectural poverty extends to the poverty of the pictorial work, which was almost null.

While in other cities specialized art centers were established, such as the Escuela Quiteña and the Escuela Cuzqueña, where the Churrigueresque Baroque flourished in painting and found delicate manifestations in religious ornamentation. In Panama, and only in the interior of the country, there were some manifestations of creativity in religious imagery, silverware and a form of Baroque, such as the Church of San Francisco de la Montaña.

Due to its transit and commercial function, the Isthmus suffers, since its colonial origins, a very poor artistic and cultural richness.

What would be the aesthetic values of the new artistic manifestations in the first years as a free republic?

At the time of the separation in 1903, the social, economic and cultural conditions of the Isthmus were deplorable. The earthquake of 1882 destroyed half of the urban core and the interior of the country was in abandonment. The epicenter of economic and political activity was the site of transit. The aesthetic criteria of the dominant group was extremely poor and they were satisfied with printed reproductions of saints or biblical events. Commercial activity was imposed as a modality of interaction and as a collective project, leaving education and cultural manifestations in the background. French and Italian influences only appeared at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century with the influx of young people who went to study in Europe.

What was the impact of European expeditions and explorers on the arts?

The interest in the construction of a canal through Panama produced a series of expeditions and explorations, particularly English and French, whose objective was to describe the natural, geographical, social and urban environment of Panama. The most important, but not the only one, was that of Armand Reclus (1876-1878).

The result of these expeditions in the Panamanian 19th century offers two thematic elements for those concerned with art.

The construction of the railroad (1850-1855) and the French onslaught of the Canal (1877-1896). The first, with its encampments, racial plurality and track layout, will be a valuable component in the works of transient artists. The other fact, which is vehemently expressed by the artists of the time, is expressed in the clash between the exuberant nature of the tropics and the machinery, which offers a moving vision of the transformation of the natural world by man.

Can we speak of Panamanian painting in the 19th century?

The painting of the Panamanian 19th century has as exponents foreign artists who used the Isthmus as a point of embarkation to other lands, so we cannot say that it is a “Panamanian painting”, since its realization and its methods correspond to concepts developed in other countries and that are interested in thematic aspects of the country.

From the period of the French Canal there is a good number of drawings executed by French artists. The published editions of Exploraciones a los Istmos de Panamá y Darién, by Armando Reclús (1876-1877-1878), and El Canal de Panamá, by Napoleón Bonaparte Wyse (1886), show a series of wood engravings, which were based on the descriptions made by the authors. In some cases, photographs and daguerreotypes were used as sources of description.

Barclay and H. Clergert executed drawings of religious buildings and public places, M.D., an acronym that identifies a draftsman from Mississippi named Midleton Davis, known for his illustrations for newspapers in the southern United States. Davis is the author of Negrito Fumando y Mamando, a beautiful custom painting of great drama; another work of careful elaboration is Darienita en la cocina (Darienita in the kitchen). E. Roniat made a series of works called Tipos del Darien, where he exposes the physiognomic features of zambos, mulatos, cholos and Indians. The works of G. Villier collect elements of the landscape and ways of life of the Panamanian rural environment. La Constancia, Caída del Caimito and Chepigana are representative works.

The description of the construction works of the Canal are collected in drawings by Vignal, who imprints great dramatism to the encounter between men, machine and nature. His drawings Excavator Bebert, Great American Dredge and Marine Dredge at the entrance of the Mindi River, and Canal works in Bajo Matachín and Bajo Obispo are well known. Of the stay of Charles Laval and Paul Gauguin in the Isthmus, works are unknown, however, according to testimonies in Gauguin’s correspondence, Laval dedicated himself to execute portraits of Canal officials in order to obtain money to travel to Martinique.

Other artists, attracted more by urban life, depict the costumbrist details of Panama City. Charles Parson drew in 1859 The Cabildo and Streets of Panama; other works of this artist are: Barrio de Santa Ana, Puente antiguo de Panamá Viejo and Rampas de las playas de Panamá. Theodore Weber is the author of a view of the old city walls.

From the year 1858 dates the work of F. Schelesinger Vista de la Ciudad de Panamá, lithograph whose sale was promoted by the Estrella de Panamá.

Of note are the works of Bayard Taylor, a native of Pennsylvania, who in his brief visit of a day and a half in Panama City, left as testimony of his concern for colonial architecture, the drawings of the Ruins of the Jesuit Convent and the Church and Convent of Santo Domingo in Panama.

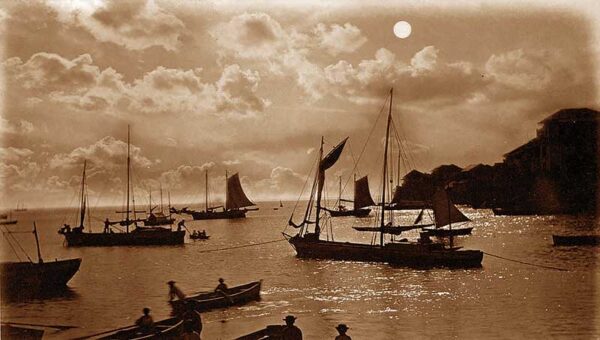

The transisthmian route in the context of the gold fever, had great attraction for the artists of the time, the work of Robert Tomes, Panama in 1855, contains a drawing of Frank Marryat titled Crossing the Isthmus, and a Landscape of the Chagres River. Fressenden Otis is the author of several drawings including First Cabin, Gatun Station and Paraíso. In that same period, four painters arrived who were to leave testimony of life on the transisthmian route, they are the German Charles Christian Nahl, the North American Albertis de Orient Brower, and the French Ernesto Charton and William Leblanc. It is important to mention the photographic work of Eadweard Mubridge, a disruptive technology at the end of the century, who took remarkable shots of Panama City at that time.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Epifanio Garay appears on the scene. Why is he important?

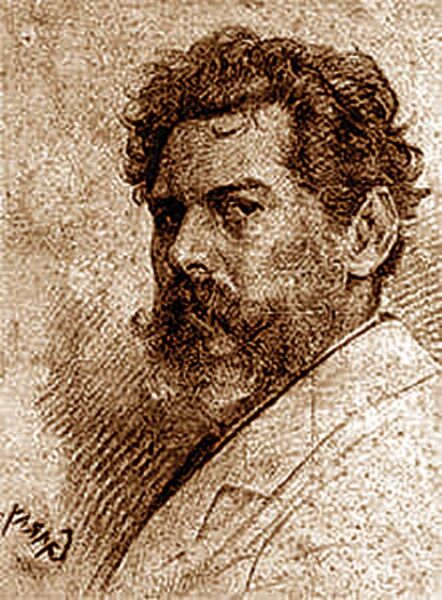

I consider Epifanio Garay as the precursor of the plastic movement in Panama and the generator, among the youth of his time, of an authentic concern for artistic manifestations, especially painting. Born in Bogota in 1849, he received his first painting lessons from his father, Narciso Garay, and later from the master José Groot. After winning first prize at the Bogota Exposition in 1873, he moved to Panama to participate in the realization of some works commemorating the independence of the Isthmus. As a result of his contact with French painting, his work is marked by academicism, characterized by the excessive care of drawing and form that predominates over light and color, and not by the innovations of Edward Manet, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir, of the French plastic movement. It is clear from this background his predilection for portraits and his little interest in landscape or urban life.

His painting is characterized by the use of strong light contrasts in which the use of chiaroscuro in the environment and the image achieves an atmosphere with a certain poetic evocation. The use of thick layers of oil paint and the insistent effort to highlight luminous points that concentrate the attention on the image establishes umbrageous visual correlations of mystical solemnity, accentuated by the cut he makes of the physiognomic features on which he concentrates the main visual focuses, leaving the surroundings as a secondary element of support to the composition. From the academic and technical point of view, his portraits lean more towards a romantic conception, due to the use of light and color and the subjective intimacy that he imprints on the image, the majesty of the neoclassical.

Among his best known works in our environment we can mention Portrait of Bishop Victoria, Portrait of a Girl, Buenaventura Correoso and his Lady, Portrait of Nicole Garay and Portrait of General Tomás Herrera. Much of his work is in private collections and museums in Colombia, where he painted religious works such as the Altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin in the Cathedral of Bogota. Garay is the great master and precursor of Panamanian painting in the 20th century.