Ethnic Groups’ Contribution to the Panama Canal

Due to its transit nature, Panama has historically favored the interaction of diverse ethnic groups that have enriched our culture. […]

Due to its transit nature, Panama has historically favored the interaction of diverse ethnic groups that have enriched our culture.

Over the course of time and due to multiple circumstances, immigrants arrived in our territory in search of a prosperous future.

The arrival of human groups from different parts of the world is also linked to the desire to find a route linking the Atlantic with the Pacific, as in the case of the Camino de Cruces and the Camino Real, in the 16th century.

Later, in the 19th century, the United States studied the possibility of linking the oceans by means of a railroad, as an alternative route in the midst of the California gold rush.

From Asia

Part of the labor for the construction of the transisthmian railroad was brought from China. This is how the arrival of Chinese to Panama was recorded, starting in 1852.

The best known and most documented event was the arrival of the Sea Witch, which reached the Panamanian Atlantic coast with more than 700 workers for the construction of the railroad.

“In Panama we are all immigrants; at some point all our ancestors emigrated, except for the original peoples, who are really the inhabitants of the isthmus,” explains Johnny Wong, a Canal retiree who collaborates with Chinese community associations in Panama.

According to historical records, these immigrants arrived “mainly from southern China, because that’s where they embarked from. There was the Portuguese colony in Macao and the English colony in Hong Kong, and that attracted labor from southern China,” he explained.

“That’s why the food we know in Panama as ‘Chinese food’ comes from that region of Canton in China,” Wong added.

The construction of the railroad began with local labor, but given the size of the project, personnel were recruited from Europe and China.

As Johnny Wong explains, recruiting agents “promised them heaven and earth, and so many arrived duped or with contracts that they had no intention of fulfilling“.

This first migration marks the beginning of the Chinese presence in Panama, and with it, the growth of a community that has participated, since then, in the development and growth of our country.

After the construction of the railroad, many “left behind the pick and shovel and went into business”.

With the construction of the French Canal, they returned to look for people to work, but, as Wong explains, “there was already a history of mistreatment, so the local governors, like those of Canton, began to prohibit going to work in this French work; however, many emigrated to Macao, which was a Portuguese colony; and from there they were shipped to Panama“.

The Afro-Antillean legacy

The origin of Afro-Antilleans in Panama dates back to the time of the Spanish Crown.

Some historical sources report the participation of a slave named Ñuflo de Olano who accompanied Vasco Núñez de Balboa in the expedition that sighted the South Sea in 1513, a fundamental fact for Panama to become a transit route.

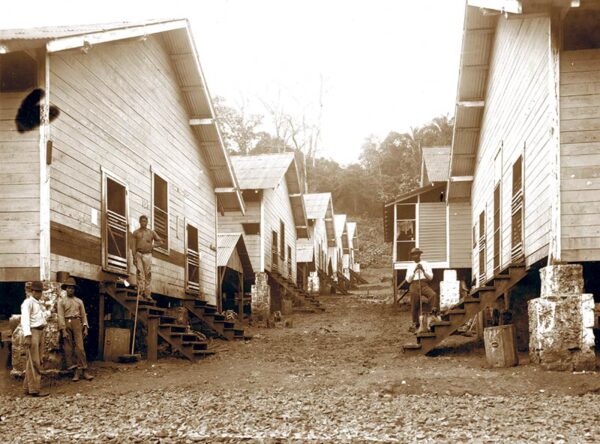

At the beginning of the 19th century, immigrants from Caribbean islands such as San Andres and Jamaica founded Bocas del Toro. Around 1850, another large number of immigrants arrived in Panama for the construction of the railroad, which led to the founding of the city of Aspinwall, today the province of Colon.

A new wave, even larger, arrived in our country in the 1880s for the construction of the French Canal, according to data from the Society of Friends of the Afro-Antillean Museum (SAAMAP).

According to SAAMAP, “it is recorded that under French control of the Canal project, 12,875 workers were on the payroll, of which 10,844 were British Afro-Antilleans: 9,005 Jamaicans, 1,344 Barbadians and 495 Saint Lucians”.

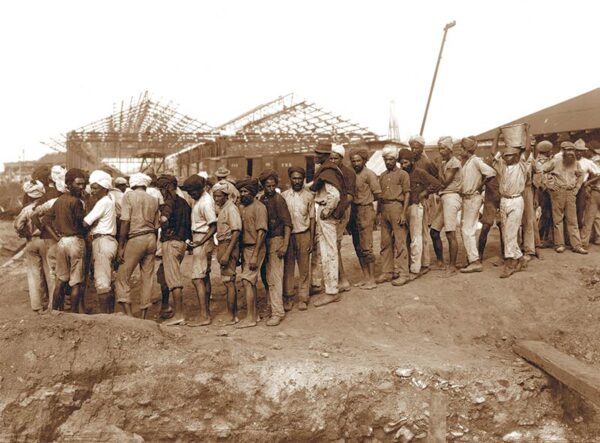

The contribution of Afro-Antilleans to the construction of the Canal, already in the hands of the United States, was crucial. Between 1904 and 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission employed 45,107 people, mainly from the Antilles, as well as from Europe and America. During that period, 31,071 Afro-Antilleans were employed.

Their hard work was vital, in the midst of inclement weather during long days, for the excavation of the Culebra Cut and the construction of the locks.

One of SAAMAP’s main tasks is the preservation of the Afro-Antillean Museum of Panama, where the historical memory of the role of Afro-Antilleans and their influence on our culture is kept.

According to SAAMAP’s president, Arcelio Hartley, “preserving the Museum is preserving our history; it is making the community continue to be present; highlighting that this ethnic group participated and had a real and significant contribution in our history. It is necessary to maintain it so that future generations can discover and appreciate what their ancestors did”.

Spanish labor

The first Spaniards to arrive on Panamanian soil date, naturally, from the 16th century onwards. However, in modern times, Spaniards – among other Europeans – contributed their labor during the construction of the Panama Canal.

Most of those who worked on this project came from Galicia. The incorporation of Spaniards into Panamanian culture became more palpable with the founding of the Sociedad Española de Beneficencia in 1880.

“After the Afro-Antillean, Spanish participation was the most important,” notes Francisco Sieiro Benedetto, a researcher and history graduate with a doctorate in American history.

According to official records of the time, 8,298 Spaniards were hired for the construction of the Panama Canal, “most of them Galicians, although they also came from the Basque Country and Asturias”.

Sieiro Benedetto is the author, together with Carolina García Borrazás, of the book Galicia en Panamá: Historia de una Emigración. García Borrazás has a degree in Education Sciences and a master’s degree in Migration Studies.

According to the authors, “everything takes place between 1836 and 1860, when five million Spaniards migrated to America”. The main destinations were Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, among others. Panama was a little known destination, “but it was very attractive, especially when the construction of the Panama Canal began”.

The recruitment was commissioned by John F. Stevens who sent a recruiter who published a series of advertisements in newspapers offering the jobs.

“The advertisement gave all the conditions, especially how well they would be paid: 20 cents an hour and that they would work eight-hour days, although later it turned out to be many more. They were asked to be between 25 and 45 years old. Most of them were peasants, and they worked with pick and shovel,” Sieiro adds.

“There was an important migratory transfer between Spain and America. It was mostly by boat, with Columbus as the only destination. Departures were from Vigo, Galicia, Santander in Cantabria, from the Iberian Peninsula. Galicians, Asturians and Basques.

“Despite the climate of Panama they adapted well,” he noted.

The incorporation of Spaniards into Panamanian culture became more palpable with the founding of the Spanish Charity Society in 1880.

Thanks to the contribution of the different ethnic groups to the culture of our country, the construction of the interoceanic waterway was possible, so its legacy will remain unchanged over time.

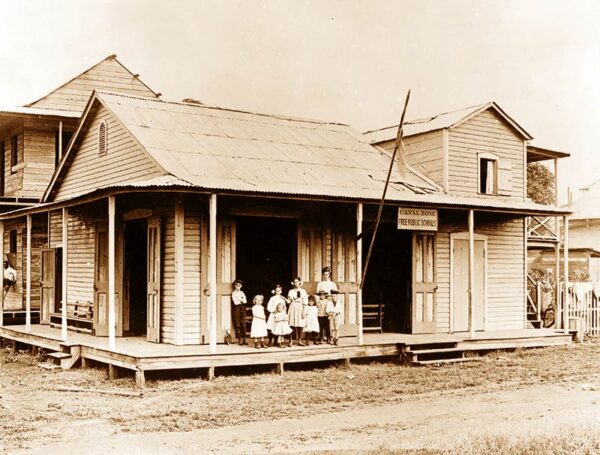

For this reason, the Panama Canal has identified some areas of the Agua Clara Observation Center (COA), in Colon, so that different groups of immigrant descendants who wish to erect a monument in honor of their ancestors, can do so on their own initiative. In this way, the legacy of our ancestors to the culture of Panama and its interoceanic canal is honored.

In addition, work is being done on a monument dedicated to the Canal workers in the Balboa area. The latter will be financed by the Panama Canal.